Zero and Other Fictions Read online

Page 2

Lai Suo never forgot those words. As he lay in bed, recalling the past, Mr. Han, Fatso, the Japanese, and the stern-looking judge, his tears once again began to fall.

“Don’t bother your dad,” he heard his wife, who was standing by the door, say to their twelve-year-old daughter.

“Why is he making such strange noises in his sleep?”

“He is not feeling well.”

A little while later, he got out of bed and went to the bathroom to wash up. The bathroom was always immaculate. Distorted faces were reflected in the squeaky-clean mosaic tiles (facing the wall, he shook his head). The faces moving on the tiles metamorphosed in unpredictable ways, suddenly a toothy grin, eyebrows suddenly falling out and chin stretching, nostrils suddenly pointing upward, revealing a walnut-sized Adam’s apple. “I’ve become thin.” He sighed. He stood on the scale next to the bathtub to weigh himself. The needle stopped at 46. It was the same as last month’s record. But last month he had not worn a stitch of clothing. He had squatted naked on the scale while singing, “Sitting alone at night beneath the lamp, a cold wind blows over.…” He had sung only half the verse when his wife knocked on the door. “Ah Suo, what are you doing in there?” He threw open the door and his wife let out a piercing scream, and, looking quickly right and left, scolded, “You’re going to die!” So now when he took off his pants and crouched on the scale, the needle spun reluctantly backward for a moment. Stepping naked off the scale, he sat on the toilet; the wet toilet seat made him shiver, sending a chill up his spine, where it bored deep into the base of his skull. Immediately he returned to the day on which he got married in 1963.

2

The bride’s face was heavily powdered, her hair permed in ringlets. Her large backside indicated that she would later bear a great number of progeny for the groom. The wedding reception that day went smoothly, and the big gold “double-happiness” character in the hall added to the atmosphere. The bride’s parents and her two brothers had come up from the distant countryside. Out of politeness, her brothers, who were chewing betel nut, spit the betel-nut juice into napkins, which littered the floor. Ah Suo’s elder brother was very excited and went from table to table with his wine cup in hand, offering toasts. His face was flushed. At that moment, he suddenly announced to all assembled that he was giving several shares of stock in his jam company to his brother. The friends and relatives applauded. He wasn’t drunk when he uttered these words. There were only two tables at the reception, and two of the seats were empty— they had been reserved for two important relatives, but they were unable to attend.

After the guests had left, Lai Suo quickly got under the covers, where he set to work stripping his bride bare. He was so intent on what he was doing that he forgot to turn off the nightstand lamp on which had been pasted the character for “happiness.” For this reason, the bride did her best, twisting and turning, looking here and there.

“Oh!” she shouted. “This is such a pretty room.”

“Hold still,” said Lai Suo, “or I’ll never be able to get this button undone.”

In addition to undoing buttons, he could also thread a needle, sew a hem, and do calisthenics, all of which he had learned in prison. This morning, fifteen years later, he suddenly bent down and tried to touch his toes. Despite his exertions, he couldn’t reach that spot twenty centimeters below his knees with his fingers. He was wearing a pair of shorts from which protruded his scrawny legs. His kneecaps looked like hard tumors. Lai Suo’s wife stared at him uncomprehendingly.

“When I was young, I could touch this,” he squatted and patted the floor, “my palms flat, without bending my knees.”

“What’s so good about that?”

Nothing at all, so forget it. At that moment he was standing absentmindedly in front of the filter in the jam plant. The needle of the pressure gauge was steadily rising. The motor below was screeching. The syrup entered the filter, which looked like a bomb, through a pipe in one end and came out a pipe in the other end. Then it flowed precipitously into a condenser suspended in the air, emerging from which it was no longer syrup but rather a mass of shiny, gelatinous substance. The whole process was reminiscent of that used by God when he made man. Perhaps there are those who would say that a fetus takes shape from the blood concentrated in the womb.

But that is not what Lai Suo’s mother thought. At only seven months, he was in a hurry to leave his mother’s belly, bawling in a world that was not yet ready to receive him. His mother, whose face was pale, lay to one side while his father stood, in only a military undershirt, continuously wringing his hands, his head covered with sweat. A drop of sweat fell on the tip of the infant’s nose—this is humanity’s earliest recorded impression of falling rain. There were some other people standing around the bed as well.

“What are we going to do? What are we going to do?” Lai Suo’s father kept muttering.

“Oh no! Why is his skin blue?” asked his second maternal aunt, who later had a son who worked for the American military advisers and therefore was absent from the wedding banquet.

“My son?” his mother said, closing her eyes. “Let me hold him.”

“You can’t hold him yet,” replied the midwife. “He has to be wrapped in medicated cloth; otherwise he might change shape.”

It was most likely on account of the medication that he became uglier as he grew, reaching adolescence late at sixteen years of age. But adolescence wasn’t all that troublesome for him. He was the smallest in his class and sat only a meter from the podium. The Japanese teacher was constantly but furtively scratching his crotch. He suffered from eczema but didn’t think anyone could see, He was wrong.

“Zhina (China)!” said the Japanese. “All of you, repeat after me.”

“Cheena,” said Lai Suo.

“Do you all know that you are not Chinese but Taiwanese?”

“But Teacher,” replied one local student, “my grandfather said that we all came from China with Koxinga.”

“Bastard,” swore the Japanese. The teacher’s saliva hit Lai Suo in the face, and when he raised his hand to wipe it off he discovered a pimple.

As the pimples began to grow, some began to fester. He was walking down the street in Dadaocheng, squeezing pimples as he walked, his face filling with red and white blotches. As he squeezed the fifth one, his companion, Little Lin, elbowed him.

“Hurry, look!” Little Lin whispered. “Isn’t that Tanaka Ichiro?”

“Who is Tanaka Ichiro?”

“The Japanese guy who taught us history two years ago.”

Both sides of the street were filled with straw mats, on which knelt Japanese with their heads bowed. All kinds of things were spread out on the mats, including costume jewelry, fans, high military boots, and dolls dressed in kimonos. Lai Suo had just turned eighteen and the Japanese had surrendered not long before that. At first the locals didn’t know what to do. Lai Suo’s father, who worked for the Japanese, was only able to collect himself several months later. He rented a house near the Central Market and got into the fruit business. Fruits are good to eat but troublesome plants. During the day, Lai Suo would push a handcart along the Danshui River, where he would establish several bases of operation. Since he didn’t possess a hawker’s voice, he’d always sit on a cushion at the head of the cart with his bare feet in a basket, where he would absentmindedly rub the watermelons the size of human heads. In the evening, he put on a pair of noisy wooden clogs and sauntered around.

“Thank you, thank you, arigato, arigato.” The Japanese would bow at the waist until their heads nearly touched the ground.

“Let’s go and say ‘thank you’ and see if he recognizes us.”

Lai Suo thought about it for a moment.

“No, that’s not nice.”

“Why?”

Lai Suo thought some more.

But something prevented him from thinking and forced him back five, ten, twenty years.…

“Is there something wrong with the machine, Mr. Lai?�

�

“Is there something wrong with the machine, Mr. Lai?” asked the factory worker again.

“What did you say? Oh, the pressure seems a bit high.”

“There are too many impurities this time making it difficult to filter. Listen to the motor.”

It was not just the motor. The sounds of the mixer, pump, and steam valve all converged into a mighty torrent of noise.

Lai Suo pricked up his ears and listened.

3

He seemed to hear a number of other sounds. His two maple-leaf ears were completely exposed to the continuous noise on the street—buses, trucks, cabs, motorcycles, as well as the occasional siren of an ambulance as it rushed by. All of these sounds knocked on Lai Suo’s eardrums as if they wanted to penetrate even deeper, but were stopped in the middle by something—it was like an acoustic tile on which was inscribed: LAI SUO, TAIPEI, JUNE 1978, TRAVELER THROUGH TIME AND SPACE.

At the time, he was riding home on the bus. The driver treated his bus like a toy and had the radio on at full volume. The speaker was right above his head. Lai Suo was curled up on the green plastic seat when a large, middle-aged woman sat down next to him. She was fierce looking, her two breasts cascaded down, and she smelled of cheap perfume. His wife used Max Factor, which he could recognize immediately. On the back of the seat in front of him, someone had scrawled several words with an eyebrow pencil: “Lonely? Call Li Meihua at 871–3042.” Lai Suo smiled to himself.

The bus stopped in front of the city office building. Lai Suo sat gazing as the receding scenery came to a halt. Several seconds later, the scenery once again began to recede. The pedestrians, gray trees, dirty houses, and long billboards all seemed as if they were being swallowed in an incomparably large mouth. As the bus crossed an overpass, Lai Suo shut his eyes for a while. When he opened them again, he was standing in the reception room of Pan-Asia Magazine in front of a full-length mirror. A small guy with a bland look on his face appeared in the mirror. The door opened suddenly and an office worker poked his head in.

“Mr. Han would like you to go to the meeting room.”

“What for? I’m here to pick up my pay and then leave.”

“He wants you to go, so you’d better go.”

“It was agreed that I was to pick up my money each day.”

“Stop with the nonsense.”

He didn’t recognize anyone except Mr. Han and the office worker who led him in. Mr. Han smiled when he saw him. He quickly lowered his head and shamefully looked at the dirty soles of his feet. Stepping on the clean tatami mats, the office worker shook his head with loathing and said, “It’s okay, step up.”

“Lai Suo!” Mr. Han stepped over and clapped him on the shoulder. “This is Mr. Chen and Mr. Lin. Have a seat. And this is Mr. Huang.”

“How long have you worked here?”

“Four months.”

“What did you do before you came here?”

“I sold fruit by the Danshui River.”

“Why aren’t you still selling?” said Mr. Han as he turned to the gentlemen sitting cross-legged on the tatami mats. “All business is doing badly.”

“I wasn’t any good at it,” replied Lai Suo. “I sometimes gave incorrect change and my voice isn’t very good.”

“Okay. You went to school, right? How would you like to be a regular office worker?”

The gentlemen looked up and eyed him. One whispered to another, “A simple, honest fellow.”

Lai Suo heard him.

A simple, honest fellow. What does that mean? On the bus thirty years later, Lai Suo listened attentively to the voices. The bus passed down a stretch of road where water pipe was being laid. Sawhorses, concrete water pipes, and excavators were piled on both sides of the road. He didn’t know how many times altogether the city had dug up and repaired the road around the municipal building. But that had nothing whatsoever to do with him. Besides, everyone ought to have something to do, something at least to keep himself busy. The woman with the big breasts was yanking fiercely on the bell cord, her bottom half pressing heavily on his shoulder. Lai Suo couldn’t help but throw her an angry look. The bell rang for quite a while before the woman finally sat down. A shadow passed in front of Lai Suo. He quickly turned to look out the window; the bus was now proceeding along a smooth, gray, monotonous highway. The scenery outside continued to recede into that large and fierce-looking maw. Lai Suo persisted with his deep, unending meditations.

“What does a regular office worker do?” he heard himself ask in his heart.

“The work is lighter and you take home an additional 100 yuan a month.”

“Why?” he asked himself again.

“Take a look at this,” said Mr. Han, handing him a thin sheaf of papers. “Sign your name at the bottom, and bring your seal tomorrow and affix it.”

Lai Suo read the first few lines.

“I vow to join the Taiwan Democratic Progressive Alliance under the leadership of Mr. Han Zhiyuan and to do my utmost for my fellow Taiwanese.… If I violate this oath, may Heaven have no mercy.”

4

Lai Suo kept on asking himself until he was exhausted. He got off the bus and started toward home. On the way, he stopped at a bakery where he purchased a large bag of peanuts and three lollipops. He could eat the peanuts on the balcony that night, and there was one lollipop for each of the kids. This one was chocolate, according to the clerk, and this one was cream, and this one was lemon. These are five-spice peanuts. What else do you want, Sir? Nothing, nothing else. But what about Lai Suo’s wife? She didn’t seem to need anything. She had everything and nothing. Sometimes Lai Suo was confused. How could anyone have a wife like his, with her energy, who always seemed on the verge of exploding, and who would hose down everything at any moment? She insisted that everyone in the family put on clean clothes each day. She patiently went through their pockets. “There’s no end to the dirty things,” she said. “If I’m not careful, I might pull out a rat one day.” As she finished speaking, she tossed Lai Suo’s hankie into the washing machine. Her aim was good—socks, ties, towels, and the little yellow school caps worn by the kids. Lai Suo shook his head, and as he stepped on the wet floor, he slid into the living room.

Although his wife was that way, thought Lai Suo, at least he could stand it, even including what happened in the deep of night; he could take it all.

When he was half asleep, she would roll over on him without any prior warning and press him under her corpulent body. Lai Suo would use every ounce of strength to free himself from the nightmare. He struggled, crowing strangely.

“Ah Suo, I rolled over on you again,” his wife said, deeply apologetic.

“That’s okay,” was how Lai Suo, who had been married only a matter of months, replied.

“Did I hurt you?”

“A little,” he replied. “I have a bad dream every time.”

“What dream?”

“It’s very weird.”

At that time, Lai Suo was standing on the floor of his prison cell, facing the wall and crying. Cold, dim rays of sunlight entered his cell through the small window above his head, falling on the soles of Fatso Du’s swinging bare feet. Du frequently scratched his toes while narrowing his eyes to fix his gaze on the weeping Lai Suo. Lai Suo had just received news of his mother’s death. She had visited him once a month in prison, bringing him things to eat and leaving with tear-swollen eyes. Lai Suo heard the news from the other side of the mesh in the prison visiting room. He couldn’t help but howl. Clenching his fists, he struck the mesh like a desperate rat until the guards came and pulled him away. His older brother wept gently on the other side of the mesh. Lai Suo walked unsteadily into his cell. Fatso Du grabbed the small box of food items from Lai Suo and had soon stuffed himself. In a good mood now, he thought about saying a few words of comfort.

“Save your strength,” said Fatso. “You still have six years and four months to cry.”

Lai Suo abruptly stood up, turned, and eyed him, his shoulde

rs heaving.

“What did you say?”

“I said save your strength. What good does it do to cry?”

“Fuck your mother!”

The next minute, Lai Suo and Fatso were rolling around on the floor. In another thirty seconds, Lai Suo was pinned under his enormity. Lai Suo struggled, kicking and shouting, his spit flying, covering Fatso’s face.

“Keep on screaming and I’ll crush you to death.”

He calmed down only at this show of malicious ferocity.

“Sometimes I dream of my mom,” said Lai Suo to his wife, who was lying beside him.

5

It was already very late and Lai Suo, who was in a good mood, was still sitting on the balcony shelling peanuts, his two legs propped up on the railing. It was the beginning of summer and the stars shimmered on the horizon and a line of headlights shone on the freeway. Lai Suo, wearing a BVD undershirt, took up the responsibility of trying to solve the riddle of life. His expression was by turns warm, cold, and confused. He was busy shelling peanuts, which he picked up between thumb and forefinger and then squeezed, making the peanut pop, revealing the white peanuts inside the shell. Lai Suo threw the shells down into the street. With the help of a breeze, peanut shells littered the entire street.

“What’s wrong with having a drink?” asked Lai Suo’s dad.

“You could end up with illnesses such as congestion of the brain, rheumatism, or an ulcer,” said Lai Suo’s mom.

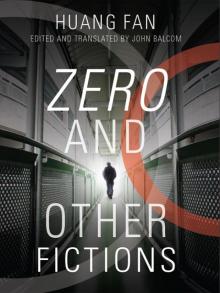

Zero and Other Fictions

Zero and Other Fictions